Economic environments are inherently dynamic, yet few scenarios present as intricate a challenge as stagflation. For those participating in the Indian stock market, understanding this phenomenon is particularly important. Stagflation represents a situation in which conventional economic wisdom often fails to provide clear guidance, and both policy compliance and investment strategies require careful consideration. This blog explores stagflation, including its meaning in economics, principal causes, historical examples, distinctions from regular inflation, and the responses of governments, central banks, and market participants to tackle it.

Stagflation is a relatively rare macroeconomic condition defined by the simultaneous occurrence of three negative trends:

The term itself is a combination of “stagnation” and “inflation.” This economic anomaly challenges traditional ways of thinking about economics, which says that inflation tends to rise during periods of robust economic growth and to fall during recessions. Stagflation, however, reflects the coexistence of stagnant growth and rising inflation, creating a particularly difficult environment for policymakers and investors alike.

| Feature | Stagflation | Typical growth period | Typical recession |

| Economic growth | Stagnant or negative | Strong | Weak |

| Inflation | High | Moderate/Low | Low |

| Unemployment | High | Low | High |

Stagflation may emerge from a combination of domestic and international factors, which often act simultaneously:

Unexpected increases in the prices of essential commodities, such as crude oil, can disrupt production and drive costs higher while reducing output and employment. India, as a major oil importer, is particularly susceptible to global supply shocks, which can ripple across multiple sectors of the economy.

Monetary and fiscal policies that are ill-suited to the prevailing economic conditions can exacerbate stagflation. Expansionary monetary policies that increase the money supply during supply shocks may further fuel inflation without stimulating growth. Conversely, overly restrictive policies may deepen stagnation, leaving unemployment high and economic output low.

Weak labour markets, slow technological adoption, and inefficientˀ allocation of resources can constrain economic expansion. These structural limitations prevent economies from responding effectively to shocks, even as prices continue to rise.

Global crises, such as wars, pandemics, or disruptions in trade, can depress growth while simultaneously causing supply constraints. Such international pressures may trigger stagflationary tendencies even in otherwise healthy economies.

Stagflation exerts pressure on virtually every economic segment:

Rising prices erode consumers’ real incomes, as wage increases often lag behind inflation. This reduces the ability of peopel to purchase essential goods and services.

Higher input costs and declining demand compel businesses to reduce their workforce, exacerbating joblessness across multiple sectors.

Profit uncertainty and poor growth prospects discourage businesses from undertaking long-term investments, including in capital markets such as the Indian stock market.

Workers may demand higher wages to maintain their living standards, further driving production costs and perpetuating inflation. This creates a negative feedback loop that is difficult to break.

Conventional monetary or fiscal tools may be insufficient or even counterproductive. Policies aimed at controlling inflation may worsen unemployment, whereas measures designed to stimulate growth may further accelerate inflation.

The most cited example of stagflation occurred during the 1970s oil crisis. In 1973, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reduced oil supply, causing prices to surge. Economies such as the United States and the United Kingdom experienced stagnant growth, runaway inflation, and widespread job losses, illustrating the severe challenges posed by stagflation.

While India has not experienced stagflation on the scale of the 1970s United States, it has faced periods with similar pressures. For instance, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, India encountered high inflation alongside sluggish growth. These conditions were largely driven by international oil shocks and structural weaknesses in industrial sectors.

| Country / time period | Causes | Inflation rate | GDP growth rate | Unemployment rate |

| US (1973-75) | Oil shock | >10% | Negative | ~9% |

| India (1980-81) | Oil / structural | ~14% | Stagnant | High (estimated) |

Policymakers face difficult trade-offs when addressing stagflation:

Central banks may raise interest rates to curb inflation, which can inadvertently increase unemployment. Conversely, lowering interest rates may stimulate growth but could increase inflationary pressures.

Targeted government spending and subsidies can provide temporary relief, but may increase budget deficits and intensify inflation.

Long-term strategies, including labour market flexibility, promotion of technological innovation, and removal of growth barriers, can alleviate stagflationary pressures. However, these measures typically require time before producing measurable effects.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) must balance inflation control with growth-promoting policies. This often involves a cautious, targeted approach, including monitoring global commodity price fluctuations and implementing sector-specific interventions.

It is important to distinguish between inflation and stagflation:

| Aspect | Inflation only | Stagflation |

| Price level | Rising | Rising |

| Economic growth | May be growing | Stagnant / declining |

| Unemployment | Usually low | High |

For investors and market participants, stagflation presents significant challenges:

High inflation coupled with low economic growth undermines corporate profitability, leading to unpredictable earnings and increased market volatility.

Fixed-income instruments may underperform if inflation surpasses interest rates, eroding real returns.

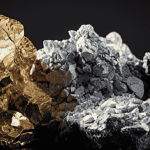

Hard assets such as gold may act as hedges against inflation, but their prices can also experience substantial volatility in stagflationary periods.

Heightened uncertainty often prompts investors to seek safer assets, reducing capital allocation to growth sectors.

Stagflation remains one of the most formidable economic challenges for policymakers, investors, and citizens alike. By defying conventional economic strategies, it affects every dimension of the economy. Although India has not faced the full intensity of global stagflation events, it remains susceptible, particularly in the context of international commodity shocks and domestic structural inefficiencies.

Understanding the definition, causes, effects, policy responses, and implications for markets is essential for informed decision-making. For Indian investors, a nuanced awareness of stagflation is critical to navigating uncertain periods, ensuring compliance, and strategically planning for multiple economic scenarios.

Gold: Tug-of-War Between Safe-Haven Demand and Macro Headwinds

4 min Read Mar 10, 2026

Bullion Demand Surges as Investors Rotate Back to Gold and Silver ETFs Amid Global Uncertainty

4 min Read Mar 10, 2026

NSE to Add Six Stocks to Futures & Options Segment from April 1, 2026

4 min Read Mar 10, 2026

Specialised Investment Funds (SIFs) in Indian AMCs

4 min Read Mar 10, 2026

Natural Gas: A Guide to India’s Trading Market

4 min Read Mar 9, 2026